Smile Stealers : A Prison Dentist Story

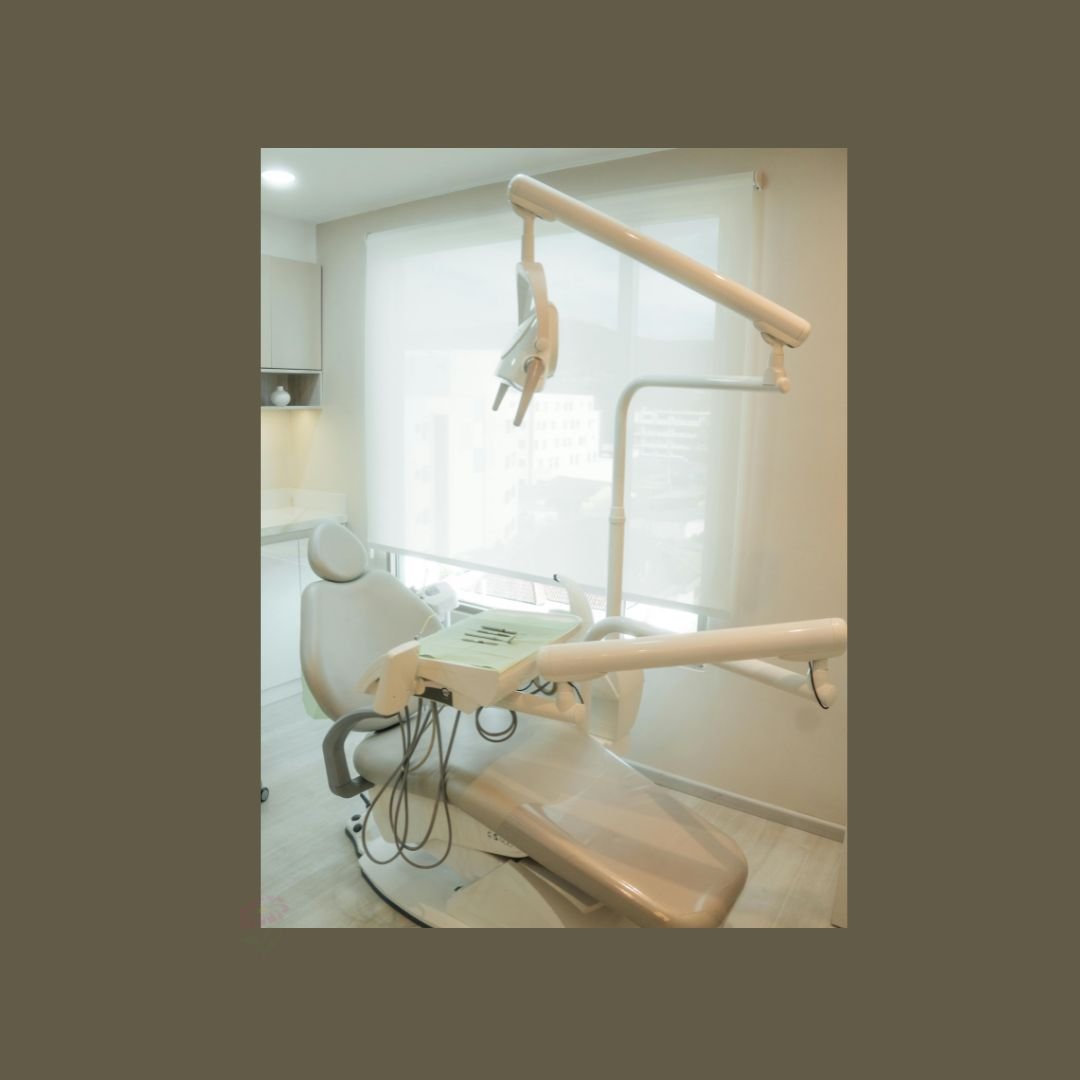

I was in jail for about .02 seconds before I realized dental care was going to look different for me now. In prison there’s a dental office, sure—but it isn’t your neighborhood dentist. When I woke up with a swollen face and an abscessed tooth, I learned fast: in there, teeth can start to feel disposable.

As a free woman, I stayed on top of my dental care. I was in jail for about .02 seconds before I realized dental care was going to look different for me now. I brushed three times a day and even fashioned dental floss out of the plastic baggies our sandwiches came in. I was in jail for a year.

In prison, there is an actual dental office. But it isn’t your neighborhood dentist. Not by a long shot.

I had been in prison for five years when I woke up with a very swollen face. It was a tooth, although I wasn’t in any pain. The unit officer, mercifully, got me into dental right away. I had an abscessed tooth. Apparently, I’d had a root canal that failed—so that explained the lack of pain. The dentist gave me antibiotics and scheduled a tooth extraction for the next week.

When the next week rolled around, I was completely better. I still had to go to the appointment, but I told the dentist and the hygienists that I was refusing the extraction. The antibiotics had worked, and I didn’t see the point in pulling the tooth.

Oh, did they get mad.

I’m not sure why the anger. But I flatly refused the procedure. I wasn’t a jerk about it. I wasn’t loud. I simply said, “Teeth aren’t disposable.”

Two years later, I woke up swollen again. Back to dental I went—different dentist, different hygienist. This dentist told me the root canal had failed and the tooth really needed to come out. He told me, compassionately, that even if I were home it would have to be extracted. He also mentioned that the previous dentist had written in my notes that I was not to be given antibiotics if the condition reappeared.

I casually told him I hadn’t gone to dental school, but I was pretty sure antibiotics were kind of the thing you do before an extraction in a case like this—regardless of how angry the last dentist was.

He assured me I would be given antibiotics. And I scheduled the extraction.

It took place the next week. No one likes having a tooth pulled. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that if I were home, I’d have options. And I really didn’t want to lose a tooth—even a back tooth that wasn’t noticeable. Maybe I was being dramatic, but that’s how it felt. The dentist numbed the area and went to work. The tooth didn’t come out easily.

I joked to my friends later that we were like lovers being separated by war. Ridiculous, yes—but it was the closest comparison my brain could grab in the moment. I felt weirdly violated. Defeated. And suddenly… without a tooth.

Two years before I went home, and maybe a year after the tooth was pulled, I broke a tooth—bottom row, not in the very front, but definitely noticeable. It broke in a way where a large displaced piece was floating between the break and the next tooth. I went to dental, and the dentist (again, a different dentist) told me there was nothing he could do. I wasn’t in pain, so he wouldn’t pull it.

I asked if he could remove the floating piece. He said no. I asked if he could at least file the jagged edges. Again, no. It took weeks for the piece to fall out. And I’m not sure if I just got used to the jagged edges, or if they smoothed out over time. It made me wonder if this was retaliation for not getting the tooth pulled years ago. What was written in my chart?

Once home, I made an appointment with a dentist I’d never met before. He spoke so kindly to me that I started to cry. I know dentists in the free world are usually really nice—but it had been so long, and I didn’t really trust him at first. Then came the sincerity. The kindness. Maybe he was just very good at chair-side manner, but I cried anyway. I was a wreck. He was the dental equivalent of my knight in shining armor.

I’m sure he’s used to patients being stressed about dental visits, and I didn’t want to trauma dump on him.

Also, he told me the broken tooth could be saved.

It looked so awful I never dreamed it could be saved. But with a root canal and a crown, I got my old smile back.

I don’t want to vilify prison dentists. Prisoners can be disagreeable, to say the least. And when medical professionals start acting hard, it’s usually shaped behavior—too many patients with horrible attitudes, too many threats, too much disrespect, and eventually the staff lose their patience… and sometimes a bit of their humanity. The result is brutal if you’re on the wrong side of the fence.

Today I’m grateful that the State of Michigan only took ten years and one tooth for my crime—because prison has a way of collecting its “payment” in places you never expected.

Thank you for reading

How People Talk Themselves Into A Crime: A Thought About the Nancy Guthrie Case

Most people don’t wake up and decide to commit a crime. They talk themselves there—one small justification at a time—until the line moves.

Savannah Guthrie’s mother, Nancy, is missing. And like everyone else, my brain immediately starts running worst-case scenarios.

Because when police say a person with limited mobility didn’t simply “wander off,” we’re not talking about someone who took a wrong turn on a morning walk. We’re talking about something planned. Predatory. Human.

This situation makes me think of a case I know about from my incarceration.

I was in prison with a woman. When she was a young mom, she was living with her boyfriend. They made the decision to rob someone. And I’ve wondered for years how that decision actually formed—because my guess is it rarely starts as “Let’s destroy someone.” It probably starts as a slow boil.

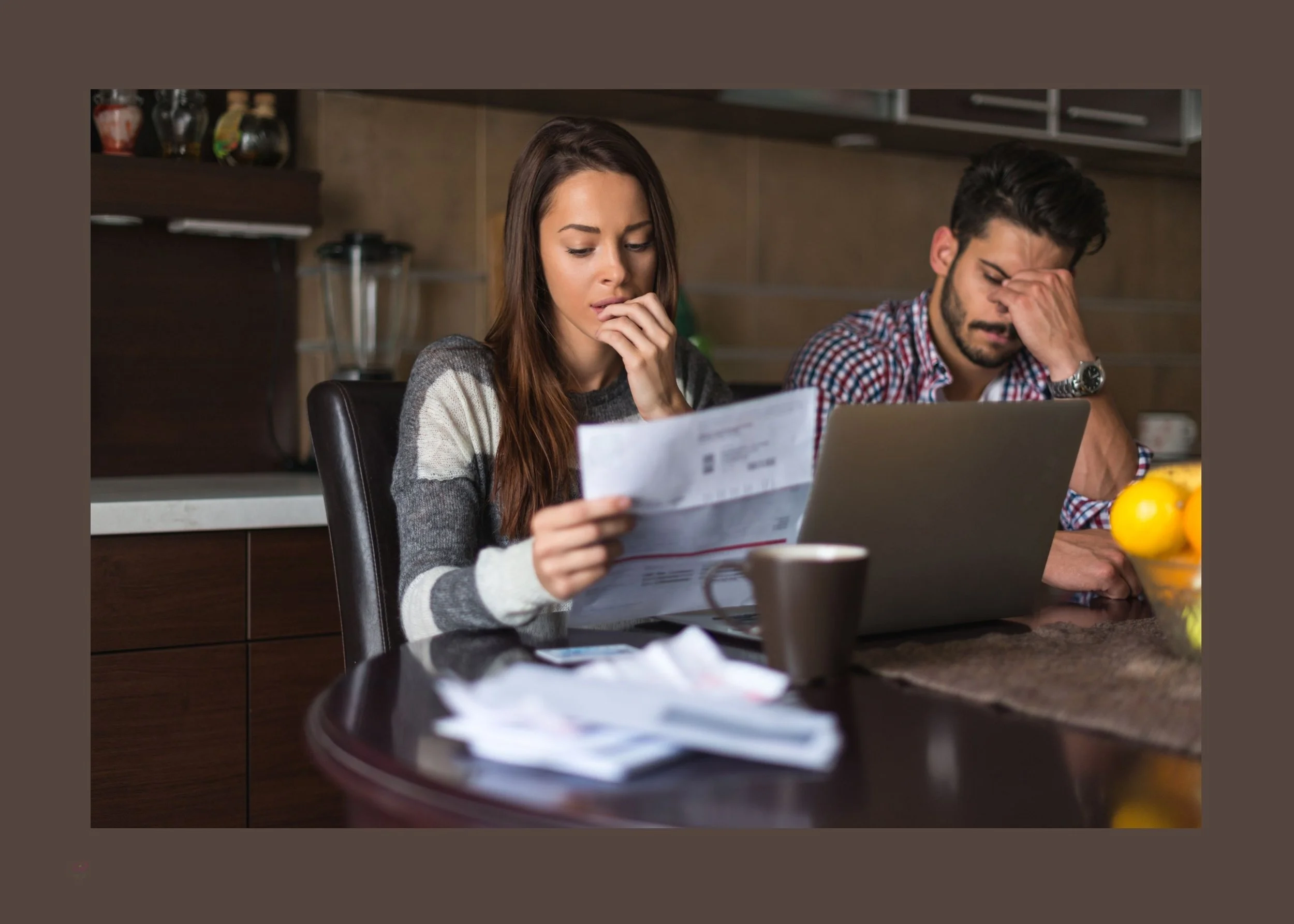

Maybe it started with the money pinch.

Not “we’re starving,” but that grindy, humiliating pressure: bills, rent, feeling behind, feeling embarrassed, feeling like everyone else got the luck and you didn’t.

Then maybe it turned into talking.

Not one big conversation. Hundreds of little ones. Complaining. Comparing. Keeping score.

I work hard and I’m not getting anywhere.

It isn’t fair that they have things and I don’t.

The rich get richer.

My son deserves to have nice things too.

And maybe this is where it shifted into resentment.

Resentment is sneaky because it doesn’t sound criminal. It sounds like a grievance. A justification. A “life isn’t fair” rant. But if you feed it long enough, maybe it stops being a feeling and starts becoming a worldview. Ya know?

Then I think the resentment becomes a shared story.

Two people feeding the same ugly narrative:

Can you believe he has a new car? He’s probably selling drugs.

Oh look at that handbag. Who is she sleeping with?

Must be nice to live like that.

They didn’t earn it.

People like that don’t even appreciate what they have.

Because after enough repetition, the story doesn’t just sit in your head. It starts to change what feels possible. What feels allowed. What feels “reasonable.”

The next step might not be action yet. It might be rehearsal, though.

Not an actual plan typed out and taped to the fridge. More like letting certain thoughts hang around without shutting them down. The kind of talk that maybe sounds like:

I’m just saying… somebody could do something at that corner store…

People get away with things all the time.

No one would even notice if…

And my guess is that’s where thinking turns into permission-ish. Not full permission. Not “I’m a criminal.” More like: it’s not that crazy. It’s not that wrong. It’s not that big of a deal.

There are names for some of this. I looked them up, because I wanted language for what I’ve seen.

Moral disengagement is the mental gymnastics that make robbing or harming someone feel acceptable:

They can afford it.

They had it coming.

It’s not really that bad.

I’m not the real bad person here.

Cognitive distortions (a CBT term) are warped thinking patterns that can fuel bad decisions:

Catastrophizing: My life is over anyway.

Blaming: If they hadn’t done X, I wouldn’t be doing this.

Minimizing harm:

No one’s really getting hurt.

Everyone does it.

I had no choice.

I’m the real victim here.

Now, back to my friend and what they did.

They somehow made a choice. A terrible choice. They didn’t just pick a random target. They looked at parked cars, found a very nice SUV with a child safety seat in the back, and decided that was the one. A “soccer mom” type. A mommy-mobile. In their minds, that target probably felt “safe.” Less likely to fight back. Less likely to be armed. Easier. They didn’t choose a pickup truck with a gun rack in the back.

When the mother came back to her car, she was taken. Thankfully, she did not have her children with her.

She was driven around to banks. They stole her money. She begged for her life. Begged to see her children again. The couple showed her a picture of her children—taken from her own wallet—as a comfort? A threat? I still don’t know.

They killed the mom.

And the woman I knew was sentenced to prison for life.

So when I hear about Nancy Guthrie, my mind goes there.

Savannah Guthrie isn’t Kardashian-level famous, but she’s famous enough that the same issue applies: people around you can know things—your routines, your home, your patterns, your “normal.” And when someone already has grievance thinking, that proximity can become a spark.

It must be hard to be Kardashian-level wealthy because you end up with nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) and confidentiality clauses for everything—contracts that legally restrict employees, contractors, and staff from sharing private details about the family. But even with contracts, I don’t know how quiet you can keep a life that visible. People talk. People brag. And you never know who’s listening.

I had a family member who did domestic help for the Post family in Battle Creek, Michigan (the cereal family) more than 50 years ago. It still comes up in conversations because it’s interesting. And I’m a talker. Is it likely that caretakers and family mention those kinds of connections too? Maybe?

To be clear: I’m not claiming that’s what happened in this case. We don’t know. Speculation can be reckless.

But is it possible someone was thinking like my friend? Put-upon, humiliated, convinced life owed them something—and then they talked themselves into a terrible action?

That’s why I keep coming back to prevention, even when the story is still unfolding.

I looked up how to stop this kind of escalation in terrible thinking, and here’s what I found:

Name the story out loud: “I’m in a resentment story.” And now that I know I’m in a resentment story, the next question is: how can I rewrite a better story?

Really think about outcomes. How does this story end? There are plenty of true crime stories out there. They almost never end the way the person imagined in their head. It’s a whole genre of cautionary tales.

And way more ideas… I won’t list them all here.

And one more thing I need to say out loud—because it’s true even if it sounds complicated: after being justice-impacted, I feel sadness and outrage for victims of crimes. Like we all do. But for the perpetrators… oh my gosh. I also feel sick about what they did to their own lives. Not sympathy that excuses anything. Not “poor them.” More like: I can’t believe you threw your whole life away for this. Because you wanted something, or were mad about something, or felt humiliated, or wanted to feel powerful for five minutes… and now your whole life is a sentence.

Because I want to recognize myself and in my own criminal case I had my own share of wrong, desperate, and catastrophizing thinking. My brain living in doom scenarios. But in my defense… it was doomy. I wrestle with this so much. How could I have stopped myself and how can I help others not get into this terrible thinking whilst living in a terrible situation.

A lot of crimes aren’t some cinematic, pure-evil moment. I was in prison for a long time, and I don’t believe there is evil in some otherworldly sense. I think it’s mainly catastrophic stupidity.

And I can’t help wondering where that went wrong.

Parenting?

Schools?

A low IQ diagnosis—or an undiagnosed limitation?

Addiction, trauma, untreated mental illness?

A partner who escalates everything?

None of that erases responsibility. But it does matter if we actually want fewer victims in the future.

Right now, Nancy Guthrie’s family is living every person’s nightmare. I’m praying she’s found alive. And I’m praying that whoever is responsible—if there is someone responsible—didn’t just destroy her life and theirs.

Because that’s the part I can’t unsee anymore: the victim loses everything… and then the perpetrator adds their own life to the pile, and their family’s life too. For nothing. For a story they let get comfortable in their brain until it felt… ok-ish.

And one last story, because entitlement doesn’t always show up as grand evil. Sometimes it shows up as something so small and so weird you almost laugh—until you realize it’s the same root.

When I first arrived at prison, a very good friend sent me 16 books. I was walking to my room when a woman down the hall asked to borrow one. I told her she could—after I read it first.

Oh did she get mad.

She cussed me out! Like the books belonged to her. For days she was cruel and angry about it. Super entitled, couldn’t tolerate being told “no". It was so beyond shocking.

But that’s the thing. It exists on a spectrum. Sometimes it’s petty. Sometimes it’s violent. Sometimes it’s “give me your book,” and sometimes it’s “give me your money.”

And I can’t stop thinking about how often the first step is invisible: a thought sitting down in someone’s mind and getting comfortable.

Thank you for reading.

Fifty-One Degrees: A Cold Prison Memory

My memory of cold is 51 degrees on a prison bed—air leaking through a pencil-wide gap in the window frame, blankets folded like armor, and the kind of shivering that steals your sleep, your focus, and your dignity.

I was cold in prison. Bad cold. The kind that doesn’t just make you uncomfortable—it wears you down.

And if you’re a victim of a crime, you might feel some satisfaction reading that. I understand. Prison isn’t meant to be a cozy 70 degrees. I’m not writing this to blame anyone or to play the victim. I’m writing it because it’s part of what prison feels like.

At WHV, the buildings are older—built in the 1970s and 80s—and the housing units are huge, like giant dorms. In a place that big, the heat isn’t consistent. Some areas are warmer, some are colder, and sometimes it feels like the system can’t catch up. I don’t think it’s intentional. I think it’s old buildings, poor design, and the reality of maintaining a massive facility. But the result is the same: staff and inmates freeze.

The windows are the worst part. They don’t seal. There’s a dramatic gap between the window and the frame—about the width of a pencil. Air comes in easily, and in winter you can actually get ice building up. Women improvise like people always do when they’re cold and stuck. We pushed pads (period pads) into the cracks, or wadded up toilet paper to create a barrier. In some units, if the officers didn’t fuss about it, we could put up a garbage bag over the window or even a cut-up shower curtain.

Where your room is located matters too. If your room is at the end of the hall, you’re colder than the rooms closer to the officer’s desk. And if you’re in the end room, you’re often given an extra blanket.

(we couldn’t wash the blankets. We exchanged them twice a year. They contained the hair from the previous owner. I always requested the blankets without small pox)

We are issued two wool blankets on our arrival day. They aren’t soft, but wool is warm. I folded my blankets lengthwise like a sleeping bag so it was four layers. Then I would put my head under the blankets, curl into the tightest fetal position, and let my breath warm me up. Once my feet were warm, I could sleep. But until then, I just shivered.

I slept with all my layers on, often including my prison ski cap and jacket. It’s strange to think about putting on a winter coat to go to bed. But we did. And not to add more complaining onto more complaining, but our winter gear wasn’t great. It wasn’t exactly “The North Face,” you know?

It may surprise you to know we could order hair dryers and curling irons in prison. We used them for our hair, of course. But also to keep warm. We would use the hair dryer in our sheets to warm up our bedding before getting into bed. It wasn’t unusual to hear the dryers going throughout the night.

We also filled a plastic bottle with hot water from the hot pot, then put it in a sock so it wouldn’t burn you. We called that our “state boyfriend.” It was warm, but if the top came off you had a wet bed and you were going to really freeze.

We would also wet a towel and put it in the microwave and then put that in a garbage bag. But that cooled off quickly.

I’m the only one I know who did this, but I’m sure there were others. I would turn on my curling iron and put it between my T-shirt and sweatshirts. The curling iron was hot. Not really hot enough to curl my hair (it was cheaply made) but hot enough to burn skin. And it did. But I needed it for warmth. I never had to have it on all night. My thought was: if I held it close to my chest, it would warm up my circulating blood and hopefully that heat would get to my feet quickly.

There was one particular day when I woke up freezing. Because there are policies about temperatures in living environments in prison, I asked for the thermometer. The officer gave it to me and I put it on my bed where I slept for ten minutes. It read 51 degrees.

Fifty-one is nice for a sunny spring afternoon. But very cold in your living space. The cold seeps into your bones. You shiver, which is exhausting. And you can’t do anything. You can’t sit and write letters because your hands get cold. Same for reading or crochet. Really, all you can do is stay under the covers. All day.

I took the thermometer back to the officer’s desk and burst into tears. She was kind and told me she had already called the maintenance department. And I was grateful.

Once, I remember, maintenance made an adjustment and it was warm in the unit. Hot, actually. Too hot. But no one wanted to complain because the cold was so miserable. But remember, whatever environment we are living in, the staff and officers are working in. So the staff let the facility know about the extreme heat.

Cold isn’t only an issue in the winter. Nope. I lived in two units that have air conditioning. It surprises me that there is air conditioning at all, and it isn’t in all of the units. When there are 90-degree days I’m grateful for it. But mostly, it’s just too cold. I’m not a fan of AC anyway. In the unit there is a huge blower that forces air into our cells. It’s both loud and cold.

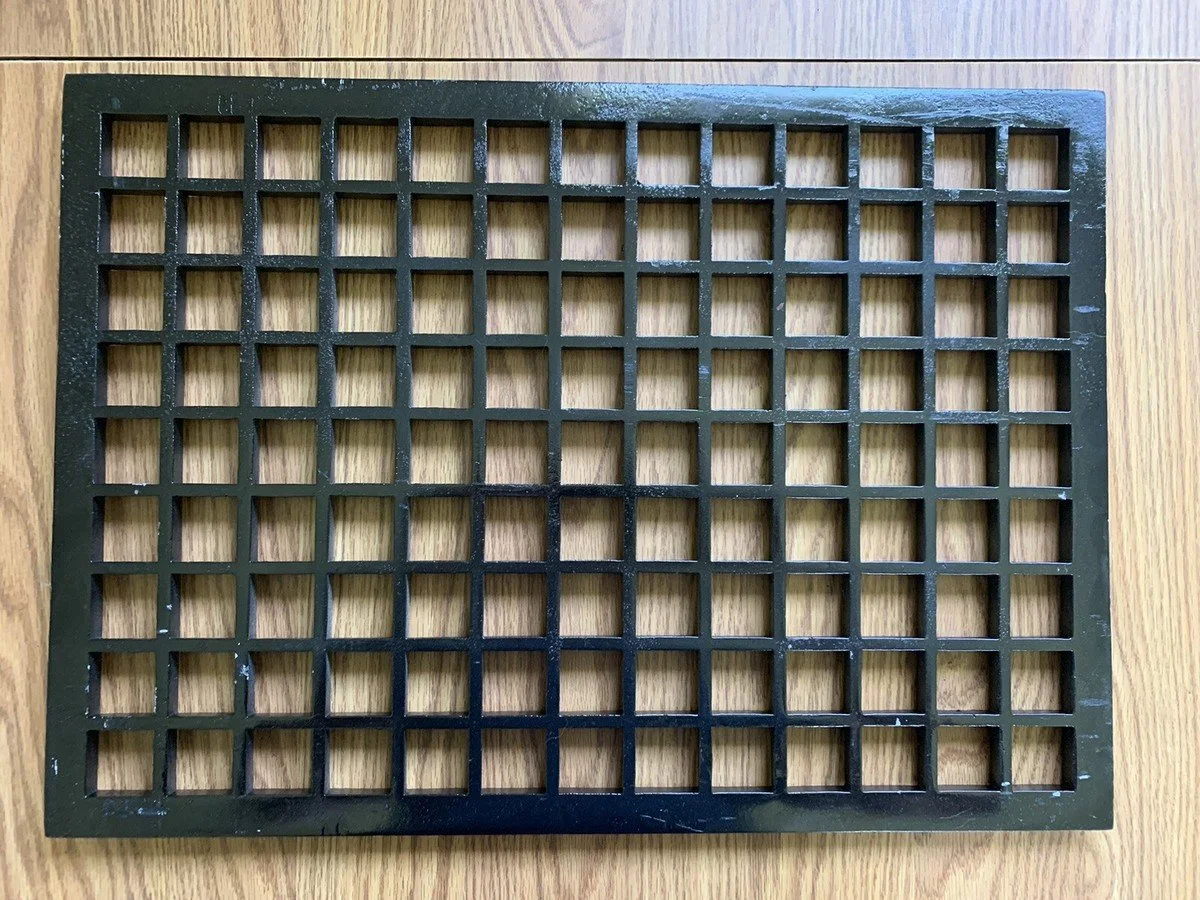

Our cells have a grate high up where the air comes in. There are ways to cover the grate with cardboard or plastic, but it’s hard. The best way is beeswax, that we use for hair, to coat over the holes. And then someone has to climb onto a locker and coat the whole grate in that stuff. I had a roommate who could reach, and I was grateful for it. The room warmed up and was quiet. It did get a bit muggy without air circulating, but I didn’t mind.

Occasionally an officer would step into the room and notice the extreme temperature difference and have us clean out the grating. Which we would do. But after some time passed it would get covered again. No one likes breaking the rules. It’s just hard to be cold.

Lately I’m seeing posts on social media about extreme cold in the prison. And it makes me remember. It makes me feel bad for the ladies still in there. I hate that for them. For anyone.

I was home a few days when my friend Margaret gifted me an electric blanket. Over two years later I still thank her for it. And it’s something I added to my list of “must haves” for inmates coming home.

Thank you for reading.

The Death of Ashley Harris A Very Sad Prison Story

She was this bright light in a tiny corner of a dark place, and it still somehow radiated hugely out. People loved talking to her. And even now, that’s what sticks with me: she mattered to so many.

I couldn’t find any pictures of Ashely so I picked this.

I have been thinking about writing this for a very long time. It’s hard and sad, and I really didn’t want to. But it had to come out. God, the universe, the fates—maybe Ashley herself—or maybe it’s just me, stuck on this. Either way, here it is.

I had two very good jobs in prison. One was being a mentor in the Acute Care Unit—the mental hospital of the prison. This is where they housed the “criminally insane,” for lack of a better term. My role was to teach skills recommended by the therapy team and to run groups like creative writing, or anything else they asked for.

My other job was Peer Observation Aide (POA). That job meant sitting in front of the door of someone on suicide watch. My job was literally to keep my eyes on them, make sure they didn’t harm themselves, and if they tried, to loudly shout for officers to come and intervene.

Both jobs required screening and approval. I was vetted for them, and I was honored to have them.

Ashley Harris was a young woman with red hair, pale skin, and a bright, easy smile. She had been on suicide watch for a long time. She was also housed in the Acute Care Unit.

From what other women told me—women who had been there longer than I had—Ashley came into prison “normal,” functioning in general population just fine. But she lost her twin sister, and that changed everything.

After that, she fell into a cycle: suicide watch, then the most restrictive environment, and back again. Because of my two jobs, I had a lot of contact with her.

And I want to say this clearly: Ashley was adored. For someone who wasn’t in general population, she had an unusual kind of popularity. The women who worked POA shifts loved her. She didn’t have a wide reach, but she didn’t need one. That was her energy. That was her vibe. She had a sweetness that felt almost childlike.

Here’s what her day-to-day looked like. She was in a room 24/7, always with another inmate assigned to watch her. Therapists checked on her daily. Officers did rounds, too. She had a lot of eyes on her and a lot of people moving through her orbit.

So while this wasn’t a good situation, it also wasn’t solitary confinement. She wasn’t thrown away into some dark corner. And I don’t know the details of her mental health. I’m not here to diagnose. I’m not here to judge the system. I’m just telling what I saw and what I know.

She had dreams. Big, huge, wonderful dreams.

When I sat with her, she loved to talk about food and restaurants. She dreamed of opening her own place someday, and we could talk for hours about it—menus, ideas, favorites, all of it.

I told her I loved books and that I’d written one. That lit her up. She got curious fast and started asking about writing—page numbers, length, how books are built.

I explained word count versus page count and gave her a simple trick: pick a book, count the average number of words on a page, and then use that to estimate how many pages her own writing might be.

She had access to crayons and paper through her therapist, and she took real joy in it. She was genuinely delightful.

At the time, I was living in a room with fifteen other women. One night, a woman came back from a POA shift and woke us with the news: Ashley had died.

Ashley was only in her thirties. It didn’t feel real. We all became emotional immediately. This wasn’t just “an inmate.” This was someone we knew, someone we cared about, someone we had watched over. We were invested.

Within an hour, I was called to the officer’s desk along with India, Amber, and Lori. The four of us were mentors in the Acute Care Unit—the same unit where Ashley was housed.

We were told a deputy wanted to see us over there. We assumed it was about Ashley, and it was.

The deputy asked us to meet with the women in the unit and offer comfort until the therapists arrived. It would be a couple of hours before they could get there. We were also asked to shut down rumors, because at that point nobody had confirmed anything beyond the basics.

Here’s what we were told:

Ashley was found unresponsive in her cell. The POA on duty became alarmed when Ashley wasn’t moving and called the officer. The officer responded quickly. An ambulance was called. CPR was performed.

The women in that unit—the ones housed near Ashley—would have seen it. The others would have heard it. In prison, bad news travels through doors and vents and yelling. People were calling out to each other, trying to piece together what was happening in real time.

It must have been terrifying. And these were already emotionally fragile women. I can’t imagine what it felt like for them—watching one of their own, one of ours, being worked on like that.

And then we were expected to step in.

We weren’t grief counselors. We were inmates with mentor roles because of our behavior and because we wanted to do something meaningful with our time. But grief like that? Trauma like that? None of us were prepared.

So we made a plan. Two of us would meet with anyone who needed it individually. The other two would set up a circle of chairs so women could come sit together, talk, cry—whatever they needed. And we would listen.

That’s what we did until the therapists arrived.

Women moved back and forth between the individual support and the group. Tears—so many tears. We asked them what they saw, what they heard, what they felt. Then we asked them to tell stories about Ashley. And in between the sobbing, there were smiles. There was laughter. Then more tears.

The hardest part in the beginning was the uncertainty. Everyone had a theory, and theories turn into “facts” in about five minutes when people are scared. So we held the line on the only honest answer we had:

We don’t know. Nobody knows. Nobody knows.

When the therapists finally arrived, the unit fell apart all over again. Of course. And I’m sure the therapists were able to give them what we couldn’t.

When we were finally released to go back to our housing unit, the four of us stepped outside and started to weep. There is no hugging in prison, and we were out on the walkway. But we just sobbed anyway. Every tear we held back while we were “being strong” in that unit came out right then.

We were never officially told what happened.

Later, when I looked it up, it appeared to be a medication issue. The family settled out of court.

If there is one thing I would tell her family, it’s this: Ashley was not alone. Every day there was someone at her door who cared about her and loved talking with her. Most days there were many someones.

And I want people to understand what that means inside a place like prison. It means she mattered. It means her name wasn’t just a number on a chart or a face behind a door. It means she made people softer in a place that trains you to harden up.

I know I’m not the only one who will never forget her. She made a difference in a very dark place. And even now, telling her story, I’m still hoping the same thing for all of us: that we leave something human behind—something kind, something real—no matter where we are.

Until we meet again…

What If We Tried It?

We already carry hopes, dreams, and longings with us every day. What if we were just a little more intentional about offering them to God—while walking, driving, working, and living

Years ago, I had the good fortune to run two marathons with Lisa Stieve. You may be surprised to know this about us—we are talkers. So imagine the hours of training runs, and then race day itself: five long hours (because we’re slow) to cover 26.2 miles. We talked about everything, but mostly about our hopes and dreams.

This isn’t us. I have a thousand pictures of us running but couldn’t find any! But this is the vibe.

Hers was to sing. Mine was to write.

As we trotted down the Betsie Valley Trail or circled the high school track, we laid a foundation for those dreams to grow. There was something about the energy of it—the movement, the repetition, the effort. Our bodies were working, our mouths were moving, and our dreams were being spoken out loud again and again. This isn’t a theology I learned or a verse I memorized, but I do believe that putting energy into our dreams helped make them real. And I’ll admit—I’m proud of that (and yes, I will still mention that I ran a marathon whenever possible).

And here’s the remarkable part: those dreams were achieved.

Lisa began singing.

And I published a book.

Looking back, though, I also see a missed opportunity.

What if we had been prayerful during those miles? What if we had invited God into that same energy—into the movement, the speaking, the effort? What if we had lifted those dreams up intentionally, prayed them out loud, written them down, or offered them to God while our feet kept moving?

Scripture often describes prayer and meditation not as sitting still, but as something carried through the day—spoken, remembered, and practiced “day and night” as we go about our lives.

Maybe the invitation is this: take the hopes and dreams we already carry and put some energy behind them. Speak them. Write them. Pray them while moving, while driving, while walking through the day. Prayer doesn’t require a marathon—or even a walk. But what if we tried it? Faith doesn’t have to be passive. God meets us in the effort, the repetition, and the willingness to bring Him along.

Not faster. Not farther. Just more intentionally—and more fully—with God.

Thank you for reading.

Michigan crime and punishment: women’s edition

Michigan may not execute people. But a life sentence here is real, permanent, and devastating in ways that rarely make headlines. Justice doesn’t always look dramatic—but it is relentless.

Michigan doesn’t have the death penalty.

That fact alone often fuels outrage when a horrific crime makes the news—especially when the accused are women who were once trusted and who violated that trust in the worst possible way. People want reassurance that justice will be severe enough. After spending 10 years incarcerated at Women’s Huron Valley, I believe I can speak with sincerity and firsthand honesty.

It will be.

When a woman is convicted of murder in Michigan, there is one destination: Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility. It is the only women’s prison in the state. And while it is not an execution chamber, it is not mercy either.

Women convicted of violent crimes are very likely to receive either life sentences or long indeterminate sentences—anything over roughly ten years, and often decades. For many, it is a place they will never leave alive.

The physical environment is stark and unromantic. Imagine something like a college dorm stripped down to its bones: concrete floors, cinderblock walls, metal desks and lockers, chipped paint, rust, and harsh fluorescent lighting. The buildings are large and house hundreds of women. Living spaces are small—often roughly 8 by 10 feet—frequently shared with another person. In many units, the toilet sits in the same room where you sleep and eat, leaving little privacy and no separation from bodily realities. The buildings are old. They are maintained, but age shows everywhere. Heating is inconsistent. The space feels cold—literally and figuratively.

Healthcare exists, but it is minimal. Some medical staff are compassionate. Some are not. Regardless, care is tightly limited by policy and cost. As women age, chronic conditions worsen. Specialized treatment is rare. Dental care is mostly extraction. Whatever teeth you have when you arrive, you will likely lose.

Prison also requires money—something the public often overlooks. Soap, shampoo, deodorant, and basic hygiene items cost money. A small television can cost hundreds of dollars. A tablet—used for email and photos from family—also costs money. Commissary food doesn’t replace meals, but it makes them tolerable.

Most prison jobs pay very little—nowhere near enough to cover basic needs. Realistically, about $100 a month from outside support allows someone to meet necessities and slowly save for essentials. Without that level of support, daily life becomes harder in ways that quietly compound over time.

Many women convicted of severe crimes arrive with limited social support. Friends disappear. Families fracture or vanish. They will live without many of the things they need and want—chronically and, for some, forever.

Inside, reality settles in. Phone calls are short and regulated. Privacy does not exist. Roommates are assigned, not chosen, and compatibility is rare. Conflict is inevitable. Loss of personal property, verbal cruelty, and intentional destruction of belongings are not uncommon parts of close-quarter living. In more hostile situations, a roommate can deliberately damage or destroy personal items and contaminate food, clothing, or bedding with bodily fluids—including urine, feces, and menstrual blood—an ugly but real form of control and intimidation in a space where there is no escape.

What does not typically happen—despite popular imagination—is vigilante violence based solely on the crime itself. Women are not routinely assaulted for what they were convicted of. But they are judged. They are talked about. Their crimes follow them. Silence is rare.

And yet—life continues.

There are jobs. Doctor appointments. Exercise yards. Church services. Classes and programs. Over time, people form routines. Prison is not constant chaos; it is sustained consequence. Day after day. Year after year. With no real escape from memory.

For the families who lost someone, nothing about this restores what was taken. No sentence balances that scale. But know this: incarceration is not a pause or a reset. It is a slow, permanent reckoning. Every ordinary day these women live is shaped by what they did—and by who they can never be again. They have completely and forever ruined their own lives.

Michigan may not execute people. But a life sentence here is real, permanent, and devastating in ways that rarely make headlines.

Justice doesn’t always look dramatic—but it is relentless.

Christmas for Misfits: My December article for the Trinity Newsletter.

I’ve experienced Christmas at both extremes—from the magic of childhood wonder to the desolation of spending the holidays behind bars. Christmas has a way of exposing what we’re missing as much as what we’re celebrating. But sometimes grace still shows up—in unexpected places, among strangers, and in simple acts of presence. That, I’ve learned, is where the real meaning of Christmas lives.

I’ve had the privilege of knowing the wonder of a childhood Christmas morning—when Santa delivered a Barbie Dream House and it felt like an impossible wish had slipped into my hands, as if magic itself had delivered it. I’ve also known the joy of having my own children wake early on Christmas morning and sit at the top of the stairs, practically vibrating—waiting for their dad to confirm whether Santa had indeed left gifts—and listening to their gasps of surprise and exclamations of excitement over dolls and fishing tackle.

And then, I’ve known the absolute desolation of the first Christmas you spend locked in a cell—followed by many more holidays that were just as gutting.

Christmas takes on a different shape when you’re behind bars. The world is out there lighting candles, baking cookies, and taking family photos while you’re staring at cinderblock walls pretending the day is normal. It isn’t. You feel it in the air, in the silence, in the way people walk around trying not to cry or snap. Some hide in their bunks. Some just sit there numb. Christmas in prison isn’t about gifts or carols—it’s about surviving a Holiday season that reminds you of everything you’re missing and everyone you can’t touch.

It doesn’t have to be a prison cell that separates you from the people you love during the holidays. Sometimes the distance is emotional. Sometimes it’s old wounds that never healed. Sometimes it’s addiction, family fractures, estrangement, grief, or generational trauma that still echoes years later. Loneliness has a hundred disguises, and every one of them can steal the holidays right out from under you.

I know what it feels like to brace for impact the moment a sentimental Christmas commercial comes on. Or when a decades-old carol sneaks up on you in a grocery store aisle and your whole body reacts before your mind can catch up.

I consider it a privilege to have lived both extremes—the wonder and the wounds.

The first Christmas I was free was not the triumphant Hallmark moment I had spent ten years imagining. My family and friends all had their own traditions, their own people, their own rhythms. I was still tied to strict parole restrictions. I didn’t know where I fit or where I was supposed to go.

Then a friend invited me to something unexpected—what I now call “Christmas for Misfits.” Although, truth be told, I was the only true misfit there. It was a gathering of several couples, a few single adults, people whose grown children lived far away, people who had already celebrated or were postponing Christmas until January. What struck me was that even though they all knew the hosts, they didn’t really know each other—so while they were new to me, we were, in a way, all new to one another.

There was food, laughter, warmth—and an unexpected ease that came from all of us being strangers in different ways. No tight-knit group, no insiders’ circle, just a room full of people quietly deciding to make space for one another.

And before the meal, the hosts—a deeply faithful couple—prayed grace over our potluck. It wasn’t long or theatrical. Just a simple, heartfelt prayer. But it hit me like a wave. I felt the emotions of the day, the strangeness of freedom, the loneliness, the gratitude… and under all of that, something else. I think it was my faith and theirs showing up at the same time.

Because when you’ve been through enough darkness, even a small beam of light can feel blinding. And woven through the sparkle and the food and the awkward introductions was the deeper meaning of the season: God shows up in unlikely places, for unlikely people, in the most unlikely ways.

Being a Christian doesn’t spare us from pain—Scripture makes that clear. The Bible is full of people who suffered, wandered, doubted, lost everything, and still somehow found God waiting for them anyway. Sometimes not to fix the situation, but to be present in the middle of it.

That’s why the Christmas story hits so differently when your life is messy. God didn’t enter the world in comfort or stability. He came into political tension, family stress, danger, and chaos. He came as a baby—small, vulnerable, breakable. Light arriving quietly in the dark.

So when I sat at Christmas for Misfits—surrounded by strangers, eating cookies and passing casserole dishes—I realized something: the magic of Christmas wasn’t just nostalgia. It was presence. God’s presence. And the presence of kind people willing to make room for someone who wasn’t sure where she belonged.

The meaning was in the air just as much as the wonder.

Some years we are the ones carrying the light. Other years, we are the misfits grateful for a place at someone else’s table.

And both are holy.

If Christmas feels distant, I hope you stumble into a “Christmas for Misfits” of your own—an unexpected room, an open seat, a flash of kindness you didn’t see coming. And if you’re in a season where you do feel the wonder, spread it generously. Someone near you may need it more than you think.

Thank you for reading.

Hail Marys and Heavenly Warfare: A Faith Reflection for the Trinity Newsletter.

There are prayers you whisper… and then there are the desperate, knees-on-concrete, “God, I need You right now” kind. The kind where silence feels like abandonment, and you start wondering if your words got lost on the way to Heaven. I’ve been there — begging, pleading, bargaining — and wondering if my prayer got tackled long before it reached God.

I was in jail. Had been for months. I was voraciously reading everything — anything to make the hours go faster. That included the Bible. One day, I came across this passage in Daniel, and I thought… wait… what???

Daniel was praying for wisdom — big, world-changing stuff. He wanted to understand what God was doing with nations and kings. And apparently, God answered him right away. But then came this part that stopped me cold.

The angel tells Daniel, “From the first day you started praying, your words were heard — but the Prince of Persia blocked me for twenty-one days.”

Hold up. You’re telling me Daniel’s prayer got blocked? Like there are some Infernal Linebackers?

I wasn’t in Babylon when I read that. I was in jail. And I wasn’t praying for global peace or prophetic insight. I was praying for the catastrophe I’d created — to and for the people I loved most in the world — and for my own hide. I needed God to hear me now — not after some cosmic turf war in another realm.

But honestly, my prayer of desperation isn’t unique to anyone. Desperation is desperation — whether it’s a broken marriage, a scary diagnosis, a lost job, or a life that’s veered so far off course you don’t even recognize yourself anymore. Pain doesn’t need a prosecutor or judge to impose a sentence.

Desperation is desperation …

So I started wondering — does that happen to us? Do our prayers ever get caught in spiritual crossfire, or is that just Bible-story symbolism that doesn’t touch real life? Because from where I was sitting, it sure felt like my prayers were bouncing off concrete walls. That verse troubled me. I wanted to believe God heard me “from the first day,” but I couldn’t ignore the delay — the silence, the waiting, the nothing. Was something blocking my prayers, or was I just not listening?

And then there’s that line from Proverbs…

“Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and lean not on your own understanding;

in all your ways acknowledge Him, and He will make your paths straight.”

— Proverbs 3:5–6

Beautiful words — but easier said than done when all you’ve got is your own understanding. When the church volunteers are gone, your cellmates might have some theology, but they’re in the same boat — not exactly the best crew to lean on for spiritual clarity.

Things happening behind the scenes.

Even today I don’t have a tidy answer. Maybe Daniel’s story means there really are things happening behind the scenes. Or maybe it means God’s timing isn’t built around my panic. Either way, I still pray — loudly, desperately, honestly. If the Prince of Persia’s on defense, I’m still throwing prayers downfield till Heaven catches one.

Thanks for reading.

When a Nap Changed Everything.

Sometimes the most faithful thing I can do is step back, trust, and let God do the work. I don’t have to hold everything together. Worry doesn’t add — it steals. Faith, surrender, and rest create the space where we allow God to move.

What a NICU Mom Taught Me About Surrender.

This was a story shared with me while I was in jail. I leaned on it many times since, and often shared it when I was in prison.

A mom gave birth to a son by emergency cesarean.

Her baby was whisked away to the NICU, and he was not doing well. She followed as soon as she was off the operating table, in pain both physically and emotionally, and stood vigil over her son.

Hours turned into days. He got worse. The wires and tubes were terrifying, but even beyond that — he just didn’t look good. This baby was dying.

The mom wasn’t doing well either. No real food, no real sleep, her body was breaking down. Still, she refused to leave his side. Her prayers were desperate: begging, bargaining, promising anything and everything. And yet, the little boy kept declining.

Finally, a moment came when she had to step away. Utter exhaustion overcame her. Before leaving, she poured out a thousand prayers and reluctantly left the room and laid down. Despite her dread and fear, she fell into a deep, healing sleep.

When she woke, she bolted back to the NICU. What she saw was completely different. The wires and monitors were still there, but her son’s color was glowing, his face alive. The nurses told her he had suddenly taken a turn for the better. Later, the doctor confirmed: he was making vast improvements.

Her belief about why it happened? She finally had to step away — and let God do the work.

She had believed she was keeping her son alive by staying at his side — that the moment she left, he would die. That fear kept her glued to his bedside. But when she surrendered, healing came.

Jesus said in Matthew 6, “Who of you by worrying can add a single hour to your life?” Worry doesn’t add — it steals. Faith, surrender, and rest create the space where we allow God to move.

In prison, our families live life without us. We worry our partners will move on. We fear our children won’t be safe. We wonder if we’ll be forgotten. I would see the struggle in my friends. Although walking around, they were "keeping vigil" with their thoughts and fears. Desperate prayers going up constantly. But like that mom, we’re not actually helping. We have no power. Instead, let God do the heavy lifting. Have faith in His plan.

Even now that I’m free, fears remain: health of my loved ones, my children’s happiness, relationships, politics, and future needs. But this story still steadies me. I don’t have to hold everything together. Sometimes the most faithful thing I can do is step back, trust, and let God do the work. This mom’s story is one example of God’s timing and mercy, not a formula. Sometimes healing comes in heaven rather than here on earth, but the call to trust Him remains the same.

“For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the Lord, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.” — Jeremiah 29:11

Thank you for reading.

Sowing In: A Faith-Based Prison Reflection.

In prison, words weren’t just words—they shaped the culture. You never spoke failure into existence, and you learned to sow prayers into others’ lives even while waiting for your own breakthrough. “Sowing In: A Faith-Based Prison Reflection” is about how that practice reshaped my faith and turned survival into something sacred.

I always knew that words carried weight, but once I was in prison it became more than just an idea—it was the culture. You never spoke bad outcomes into existence. If someone had a parole board hearing coming up, you would never say, “You won’t get a flop, but if you do it will be fine. Most flops are less than a year.” You’d get yelled at for even suggesting it. That’s how serious it was. The culture was to keep your mouth shut about failure and lean hard into the possibility of success.

This vibe.

Out of that culture grew a practice: sowing into others what you hoped for yourself. I prayed for women trying to get into programs, those with upcoming appeals, and those waiting for important visits. I prayed for the people going before the parole board—especially when my own turn was coming—and for those going home, especially when it was finally my turn to leave. I prayed with everything I had for my ex-husband and my children. My prayers for other people’s children and family members were the most reverent—almost desperate—because deep down I longed for my own children and loved ones to be covered in prayer. If their struggles mirrored mine, it felt like God was giving me the opportunity to intercede for my family through them. Looking back, you could line up my prayers with my prison years and see what I was facing—hoping for a mentorship, a move to a better unit, or a job—reflected in the prayers I offered for others.

The theology of this practice is complicated. Prayer doesn’t work like a bargain, and God isn’t manipulated into blessing me just because I prayed for someone else first. Faith doesn’t work like superstition. Still, something in the practice reshaped me. It pulled me out of self-pity and taught me to look outward, to want good things for others even while I was waiting for my own breakthrough. If God honored those prayers, it wasn’t because I had the formula right, but because I was learning to care about more than just myself.

Scripture speaks directly to this tension. Paul reminds us, “Do not be deceived: God cannot be mocked. A man reaps what he sows.” (Galatians 6:7). At the same time, we are told, “Let your requests be made known to God.” (Philippians 4:6) and “Pray without ceasing.” (1 Thessalonians 5:17). These verses point us away from superstition and toward trust: God hears because He is faithful, not because we’ve stacked up enough prayers in the right order. Jesus Himself warned against turning prayer into a formula, saying, “When you pray, do not heap up empty phrases as the Gentiles do, for they think they will be heard for their many words.” (Matthew 6:7).

Prayer. Also Pray-er

The heart of prayer is not bargaining but relationship. Intercession is a holy calling—we lift others before God because Christ intercedes for us (Romans 8:34). So while my practice inside prison was imperfect, the impulse to pray for others pointed me toward something true: prayer reshapes us, and God in His mercy works through even our flawed understanding to draw us closer to Him. And His grace means we often reap more good than we deserve, because the harvest of His love is greater than the seeds we plant.

Thank you for reading.

Panties: A Jail Story

In county jail, even your underwear isn’t really yours. Twice a week, the officer rolled a cart through, swapping out dirty clothes for “clean” ones that had already been on someone else. Sometimes those panties came back stretched, sometimes… altered. Let’s just say nail clippers in a toilet stall can turn Fruit of the Loom into a whole new size.

When I was in county jail, they issued everything: socks, panties, bras, t-shirts, pants, sweatshirts. Everything orange, everything standard-issue. The undergarments were basic Fruit of the Loom — nothing fancy. Some jails will let you have your own undergarments or purchase some, but not ours.

I’m a small woman, and at that time I was tiny. I'd lost a lot of weight because, well, I was going through something. The smallest size panties they had were a size five. Twice a week, the officer would come around with a cart, collect our dirty clothes, and hand out “clean” ones. I put that in quotes because they weren’t yours — they were just whatever came back from laundry. If another woman wore size fives yesterday, I might be wearing her panties today. I had to just trust that the laundry got the job done. It was gross, but there was no alternative.

Our cell had eight to ten women. You got to know each other’s sizes. Some of the women were much larger than me — tall, big-framed, or heavyset. But when laundry came, a few of them would ask for panties in size five. The officer would laugh out loud: “There’s no way you wear the same size panties Stapleton does.” But they’d insist, swearing they were a five.

Here’s where it got weird. I started getting “fresh” pairs but they weren’t just stretched out — they’d been altered. Cut at the waistband. Someone (a few of them?) had figured out how to take nail clippers (available upon request from the officer) into the bathroom area, where there was a little privacy, and slice the elastic so the panties would fit.

Just like this.

So, yes — women were cutting up jail-issued underwear with nail clippers just to prove to themselves (or maybe to the world) that they were a size five.

The whole thing was equal parts disgusting and absurd. But that’s jail. People cling to their narratives, even if it means mutilating a pair of Fruit of the Looms in the toilet stall.

Thanks for reading

Playing Chess in King Henry's Court: A Prison Metaphor and Story

“In prison, hope can hinge on a single conversation. I believed I was being seen as more than a prisoner—until one moment reminded me how quickly that identity can be stripped away. This essay is about that sting, the power of labels, and the fragile line between encouragement and betrayal.”

In prison, I joined a group that brought in volunteers from a local university—mainly graduate students and their professors. For years, I looked forward to those sessions. They offered us artistic outlets, creative workshops, classes for college credit, and—maybe most importantly—a break from the normal prison grind.

It was refreshing when people came in from the outside and they weren’t staff, they weren’t officers. They called you by your first name. They spoke to you like you were just a regular person. They read our writings and gave us feedback that was encouraging. They looked at our drawings and recognized our underdeveloped (or in some cases developed) talents. They looked us in the eye and said we mattered, and by their attention and presence I believed them. They told us we were smart. We all believed it.

The group also hinted they could help us find employment once we were released. We were left with the impression that they would be there to help us. They weren’t a re-entry program, but there were some connections and a willingness to help—they were part of a university, after all. That mattered to me. I have a bachelor’s degree in science, and I worked for a short time in both academia and industry. I wanted to get back to research. I wanted a job that made me feel like me again.

And suddenly here was my chance to get it back. I had this vision of working alongside a patient PhD in a lab doing meaningful research—catching up on the latest methods, bringing my skills current, and earning a living wage. I pictured a mentor surprised to find someone eager to throw themselves into the work—whatever hours, whatever it took. What I pictured was… redemption.

But in prison, you don’t have power. It’s like living in the court of King Henry VIII—you have to maneuver carefully, scheme quietly, and find ways to stand out without overstepping. Everything you ask for feels like strategy—like a game of chess. You rehearse, you rewrite, you plan your timing. So I carefully prepared how I would approach the director of this program. I waited years until it was closer to my release date, then I waited until a day she was in the prison. And then a moment when she wasn’t swamped by inmates or rushed out by officers. Then I made my move.

I told her about my degree, my experience, and how I’d been out of the field for years but was teachable and willing to do whatever it took to catch up. I tried to show determination, making it clear I wasn’t asking for a handout—I was asking for a chance. If I ever had anything close to a natural talent, it was research. The whole exchange was my most sincere and desperate elevator speech, offered in the few seconds I hoped might change everything.

She paused, she looked at me, and she carefully said: “Well, yes, we do help people get jobs… but more like at a restaurant, or maybe retail.”

In communication theory, they call this a disconfirmation moment—when someone denies the identity you know to be true about yourself. When I said, “I’m a scientist,” what she didn’t say, but communicated, was: “No, you’re a prisoner who can maybe work as a waitress.”

It wasn’t just the words that crushed me—it was the look. Up until then, I thought she saw me as a person. In that moment, I realized she only ever saw me as a prisoner. My place wasn’t the same as hers. It wasn’t in a respectable position in her university.

From a normal citizen’s perspective, maybe the director was being pragmatic. People assume that committing a crime closes doors to higher-level professional roles, especially those tied to trust and credentials. To them, her words might sound like realism, not betrayal. But that’s not how it felt to me. The power of the betrayal was in the gap between what had been implied and what was delivered. Hope had been built, and that was my mistake. I had been in prison a long time. I knew better.

This was the director, and that made the moment sting more. It didn’t make me think the whole program was worthless—it wasn’t. The classes, the encouragement, the art, and the chance to feel like a person again were real gifts. But this exchange exposed a seam in the fabric, a reminder that no matter how hard I worked or how much I hoped, the word prisoner still shadowed everything. The harsher label of felon would trail me long after release, closing doors I believed she might help open. In that moment, I realized she hadn’t transcended that line the way I thought she had.

Still, I believe in the program, and I believe in her and the good work she has done. I think she would celebrate any success I, or others from this program, achieve. I wonder if she ever thinks back to that moment the way I do. Some interactions linger, the kind you keep turning over in your mind to make sense of. I walked away from that conversation with heavy feelings. And because I believe she is the kind of person who would, I trust she did too.

Thank you for reading.

Held: A True Cliffhanger Story

My foot slipped in the mud, and suddenly I was hanging off the trail—legs scrambling, hands clawing for something solid. Below me was just… abyss.

Kilimanjaro

While preparing for a climb up Mount Kilimanjaro, our group planned a day hike up a smaller mountain in Africa. The trail we followed wrapped around the mountain, and as we came around a bend, we saw that a section of the path had been washed away by recent rains. It wasn’t a massive drop—just a muddy slide where the trail had broken—but it was enough that we couldn’t simply walk across. We had to jump.

The guys in the group jumped with no issue. I would have too. I’ve been a dancer and athletic-ish my whole life. But our guide and friend, Joe, looked at the path, then looked at me. I’m much smaller than the other guys, and he made a call—he offered his hand. He wasn’t comfortable with me jumping without help.

Holding someone’s hand while jumping sounds simple, but it threw me off just enough that I didn’t land quite right. My foot slipped in the mud, and suddenly I was hanging off the trail—legs scrambling, hand clawing for something solid. Below me was a long stretch of mud sliding out of sight. It wasn’t a fall to certain death, I don't think—just the kind of uncertain death. Or maybe it wasn’t death at all. Just… abyss.

I didn’t know where it led, only that I didn’t want to find out.

It was loud in my head—rushing blood, startled voices, panic. And then, through all of it, I heard one steady voice:

“I’ve got you.”

And again, more firmly:

“I’VE GOT YOU.”

When I looked up, Joe’s grip was strong, and I could see it in his face—and as I looked to where his hand gripped mine, my brain finally registered it. My panicked, mammalian, prefrontal-survival-mode brain caught up just enough to understand: he really did have me. He had me. I realized my panic and flailing were actually making the situation worse—causing a bigger problem than the slip itself.

I stopped flailing, took a breath, and he easily pulled me back onto solid ground.

Later, as I thought about what happened, I realized how often we try to save ourselves in our own strength, all while God is already holding us steady. In moments of fear and uncertainty, we may thrash and panic, forgetting the One whose grip never slips.

Joe’s voice reminded me of God's: calm in the chaos, firm in the storm, saying simply, “I’ve got you.”

Thank you for reading

Tomato Witchcraft and the Compost Gospel-A Prison Story

In prison, I planted tomatoes but never tasted one. The best ones I ate were never mine. Sometimes the real harvest isn’t the one you grow.

There was a corner of the prison that didn’t quite feel like prison. Not really. It was a building that housed the Building Trades program and the automotive shop, tucked far enough from the main compound that, if you squinted and ignored the razor wire and the matching uniforms, you could almost pretend you were somewhere else. Almost.

Inside, there was one officer posted up in a little office, but for the most part, it felt like our space. We learned how to build simple projects, the basics of NCCER (National Center for Construction Education and Research), and the gospel according to OSHA. But beyond that, we were responsible for the building and the yard. We even had a small patch of ground to care for. It wasn’t much, but it mattered.

Now let me be clear: I am not a gardener. I have no use for flowers—other than that they’re pretty and I totally gush when boys give them to me. But when our instructor didn’t object to us planting vegetables, my ears perked up. Tomatoes? Real tomatoes? The only tomatoes I’d seen in prison came in a plastic bag, two sad soggy slices meant to dress up a sandwich. I was grateful for them, don’t get me wrong—but they weren’t real tomatoes.

Then came the lifer. A woman who had been down longer than I’d been legally allowed to vote. She was a tutor in Building Trades and had somehow—don’t ask me how—come across a handful of cherry tomato seeds. I didn’t ask questions. I just found a spot near the flower beds and planted those seeds like they held the secret to parole.

I hovered. I prayed. I watered. I picked up worms and relocated them to the garden bed like a dedicated, trembling, gagging worm chauffeur. (For the record, I loathe worms. I made actual guttural sounds handling them.)

Then came sprouts. Tiny green promises poking through the dirt. I was ecstatic. I dragged the lifer tutor out to admire my work. She gave the garden a once-over and promptly informed me that all but two of the plants were weeds. I’d been mothering weeds. Hovering, praying, weeping over weeds. It was the thrill of victory, immediately followed by the face-plant of defeat (see what I did there).

Only two tomato plants survived. But I kept showing up, whispering to those plants like a delusional tomato witch. I even got on the ground and pressed my nose to the leaves. And they smelled like tomatoes. Earthy. Honest. Hopeful.

And then I “graduated out.” Finished my coursework. Booted from the program. No warning. No final harvest. No tomato.

But here's the twist.

Just around the corner from Building Trades was the Horticulture Department. They grew real vegetables. Lots of them. Over 15,000 pounds, according to the latest brag sheet. And we all shared the same compost pile.

One day, my friend and I were hauling yard waste out there, and we spotted a vine. It had tomatoes on it—technically rotting—but tomatoes nonetheless. There wasn’t a moment of hesitation. We looked at each other, nodded like bandits, and grabbed the ripest ones we could find. They were dusty, borderline sour, kissed by decay—and hands down the best tomatoes I’ve ever eaten in my entire life.

Prison changes you. It lowers your standards and raises your gratitude. You learn to savor the little things—a sunbeam on concrete, a smuggled book, a tomato still warm from the sun.

I never got to eat the tomatoes I grew. But I devoured the ones I found. There’s a lesson in that, I think.

Sometimes the fruit doesn’t come from the plant you nurtured.

Sometimes the best things come a little late and slightly off.

Sometimes you just eat the damn tomato.

Thank you for reading

The Freedom to Go to Church: A Prison Story

The moment I stopped taking church for granted. I never thought I’d have to run toward Jesus with a plastic chair—but prison changed how I see religious freedom.

In America, we have religious freedom. But for most of us, it’s easy to take that freedom for granted. Nothing made that clearer to me than prison.

When you first arrive, you're placed in a separate intake unit—an isolated, high-security area where you're locked in a tiny room with a roommate for 23 hours a day. Processing into general population takes time. For me, it took a couple of months.

This is a picture of a cell at WHV. When you first get here, it’s bare. No pictures. No hangers. No fan, no TV, not even a cup. Everything you see now is a luxury—earned over time.

But there was a bright spot: the prison allowed church services, led by volunteers from local congregations. If it was your first time attending, they handed you a Bible—a soft-covered one you held like treasure. And for women like me, that church service was more than a religious ritual. It was a lifeline.

Word spread fast when volunteers were in the building. The officers announced that church would be held in the dayroom, but that seating was limited—first come, first served. If you wanted a spot, you had to bring your own chair. So we prepared—placing our chairs by our doors, ready to sprint (well, walk quickly—no running in prison!) the moment the call came.

When they called church, it was like a holy stampede. We rushed out, chairs in hand, not wanting to miss our chance to worship. And in that moment—speed-walking down the hall with a plastic chair in my arms—it hit me: all those Sundays back home, all the chances I had to go to church freely, and how casually I treated them.

This! Exactly this but with 50 other women…

Now, I was running toward Jesus with a chair.

By the time we were carrying our own chairs into that service, most of us had already been through something—trauma, loss, shame, rock bottom. We showed up full of either deep gratitude or deep pain. Some of us were leaning hard into God. Others were just hoping He was real. But none of us were there to play church. We were there because we needed something holy to hold on to.

When I got to the dayroom, I found a spot to put my chair and sit. The volunteers were kind. They asked my name—not my number. They didn’t lecture. They just wanted to pray with us, sing with us, share the gospel with us. And they gave me a Bible.

That moment reminded me: freedom doesn’t always mean being outside prison walls. Sometimes it means being seen, being loved, being given the chance to worship.

I’ll never take church for granted again. After ten years of wishing I could sit in a real church, it’s not lost on me what a blessing it is to walk through those doors. Every opportunity I have to be here—I take it, with gratitude and reverence.

Thank you for reading

The Shank Tree: A True Story from Prison Shop Class

“It was early in my sentence when I joined the Building Trades Program, and for a few hours each afternoon, it didn’t feel like prison. We had music playing, real projects in our hands, and a teacher who treated us like people. Then came a special assignment: build a metal trellis shaped like a tree—using a plasma cutter, grinder, and welder. I was honored. But the real twist? The ‘leaves’ looked a whole lot like shanks...”

When I was in prison, I found something kind of miraculous: normalcy. It was rare, but every now and then, something would feel… almost human. For me, that something was the Building Trades Program.

It was early in my sentence when I got into the class. We met in the afternoons, and stepping into that shop felt like stepping out of prison. Music played. People were working on real projects. The teacher talked to us like we were people—not numbers or threats or burdens. Even the officer assigned to the class wasn’t looming like a tower of doom. It just felt... good. It felt like life.

Then one day, my teacher came to me with a special project.

He handed me a photo of a metal trellis shaped like a tree, artistic and beautiful, with metal leaves curling off the branches. He asked if I’d make it.

This isn’t it exactly, but close. In mine the leaves had more curve. But this is the general idea.

I felt honored, honestly. It meant he saw something in me, and I was so in. I was also really honored that I would be learning to use the plasma cutter, the grinder, and the welder. That kind of trust and responsibility wasn’t something I took lightly.

That’s how I ended up making what we now affectionately called “The Shank Tree.”

Why the name? Well, the leaves weren’t your typical oak or maple variety. They were shaped more like—how do I put this delicately—shanks. Seriously. They had that same curved, tapered look. So, there I was, plasma cutting dozens of sharp, metal leaf-shaped pieces, grinding and welding them onto a frame to bring this trellis to life.

Even the teacher laughed about it. We all did. But when we heard the warden or some higher-ups might be doing a walk-through, we’d gather up all the “leaves” and stash them in a container in the corner. Just imagine the optics: a group of prisoners making dozens of razor-sharp metal objects. Not ideal for a surprise inspection.

It took months—more than a few do-overs and plenty of help—but the Shank Tree eventually came together. It didn’t look exactly like the photo (okay, it looked nothing like the photo), but it stood tall. It was ours. And I was proud of it.

At one point, rumor had it that the finished piece would be displayed in front of the prison. I’m not sure if it ever made it all the way out there. Last I heard, it was still somewhere near what used to be the Building Trades building. Right where it belongs.

So yeah. That’s the true story of how I made a tree full of shanks in prison.

And no, I don’t recommend using it for shade.

Thanks for reading.

The Father Who Waited: A Father’s Day Commentary on the Prodigal Son

Some fathers rescue. Others wait—on the porch, in prayer, through tears. They don’t chase rebellion, but they never close the door. That kind of fatherhood is a holy ache.

Father’s Day usually spotlights strength—strong arms, strong wills, strong guidance. But the most powerful father in Scripture didn’t slay giants or swing a hammer. He waited.

Jesus tells the story of a younger son who demands his inheritance early, squanders it in wild living, and ends up feeding pigs in a foreign land. Broke and broken, he decides to return home, hoping just to be treated like a servant. But while he’s still a long way off, his father sees him, runs to him, and welcomes him with open arms, a robe, and a feast.

In the story, we tend to focus on the boy—his rebellion, his fall, his return. But tucked inside that parable is a father who does the hardest thing a parent can do: he lets go. Not out of apathy or anger, but out of love. A love that understood you can’t chain someone to wisdom. You can’t force maturity. So he let the door swing open—and watched his son walk into a dangerous, disorienting world.

That father waited. Not with crossed arms, but with hope. Not with “I told you so,” but with open arms and a robe ready. Maybe he checked that road every single day.

And when his son returned—filthy, broke, humbled—the father ran.

Some fathers rescue. Others wait—on the porch, in prayer, through tears. They watch their kids stumble and ache with every wrong turn. They don’t chase rebellion, but they never close the door. That kind of fatherhood is a holy ache.

And while we’re at it, let’s not forget—this isn’t just the story of one wayward son. It’s the story of two brothers, both a little bit jerky in their own way. One was reckless and ran off. The other stayed put but simmered with self-righteousness. And the father loved them both. Grace wasn’t just for the one who left; it was for the one who stayed angry, too. This story isn’t just about a prodigal—it’s about a parent who loved beyond reason.

And in a world that’s louder, faster, and more distracted than ever, where dads are pulled in a hundred directions and time slips by like the verses of Cat’s in the Cradle, the call to be present might just be the most countercultural move of all. That father didn’t wait for the perfect moment or make his son earn his way back. He ran. He embraced. He restored.

To every dad, granddad, or spiritual father who’s left the porch light on—we see you. Thank you for loving with patience, for letting go when you had to, and for running when it mattered most.

Thank you for reading.

Make It Your Best Day! A prison story.

“Make it your best day!”

I said it once in prison.

It went dead quiet. Then:

“Oh hell no.” “B!tch, please.”

I just kept walking—grinning.

Because weirdly, it was my best day.

My ex-husband is a high school principal, and every single morning—every single morning—he gets on the PA system and closes the announcements with the same phrase:

“Make it your best day.”

If you're a student in his school, grades 7 through 12, you’ve heard it roughly 180 times a year. Over 20 years, that’s something like 3,600 times. It's consistent. It’s uplifting. It’s wholesome.

And let me tell you about the time I said it once in prison.

Spoiler alert: I did not get shanked.

It was a beautiful morning—the kind of crisp, clear morning you can still appreciate even behind a chain-link fence topped with razor wire.

I was on the walkway, heading in one direction while a group of girls were heading the other way toward school. You know how it is—small clusters of two or three, chatting quietly, easing into their day with that slow early-morning energy.

I passed them and, channeling the ghost of announcements past, I said it. Loudly. Boldly. Cheerfully.

“Make it your best day!”

Everything went dead quiet. Like movie-scene quiet. Like someone just slapped a nun quiet.

Then I heard it behind me:

“Who the f—?”

“Oh hell no.”

“What did that b!tch just say?”

“No. She didn’t.”

“B!tch, please.”

I just kept walking. Smiling. Because in that one moment—oddly—I did make it my best day. I never looked back so I didn’t see their faces. But I imagined they looked something like this…

And somewhere out there, my ex was unknowingly being spiritually high-fived.

So go ahead.

Say the thing.

Be the weird one.

Make it your best day.

Even if it’s behind bars.

Especially then.

Thank you for reading.

Not Exactly a Bright Light and Dead Relatives Beckoning: My Near-Death Experience

I didn’t see a tunnel. I didn’t float above my body. And no long-lost relatives came reaching for me with glowing arms. What I experienced was something stranger, quieter, and somehow more profound. I was standing—if you can call it that—before a group of old men. Wise. Ancient. Watching me with the kind of gaze that sees straight through ego and into essence. No words were spoken, but everything was understood.

This wasn’t comfort. This was clarity.

It wasn’t some tunnel of light or dead relatives beckoning. I didn’t wake up, exactly—I just became. I was suddenly in this massive, ancient room. Stone walls that seemed to go on forever. The place felt old in a way that didn’t even make sense. Standing in front of me were four or five men. Not angels. Not God. But they radiated something deep and ancient. Think Plato or Socrates. I don’t think it was them, but that was the vibe. Very old, very wise, and about to give me bad news.

They said I couldn’t stay. I had to go back. Back to my life on Earth. Of course, I argued. (have you met me?) But they didn’t budge. And then one of them told me why I had to return. It stopped me cold.

My fight vanished. I just said, “Why didn’t you just say so? Of course I’ll go back.”

Then came the kicker: I wouldn’t be allowed to remember it. They told me I wouldn't remember. Furious, I said,

“Are you serious?” “What’s the point, then?”

I could feel myself about to be yanked out of that space, so I begged them to let me write it down. Just a few notes. One of them said it wouldn’t help. But I pushed harder. I knew I didn't have much time. There was an energy gathering.

Next thing I knew, a piece of paper and a pen were in my hands. It felt familiar, like I’d used them a hundred times. I wrote as fast as I could. The words flew out of me in a language I didn’t recognize—not English, and maybe not from this world at all. I wrote top to bottom, right to left, frantic to get it all down. The symbols shimmered and danced, like they didn’t want to be captured.

Then boom—I was back. Heavy. Cold. A siren in the distance. I was alive, and that felt like a punch. A sad, aching kind of punch that only a failed suicide can deliver.

And then came the fear. The kind that grabs your insides and twists. My daughter. Was she alive?

This wasn’t the Heaven I had pictured. We were supposed to be there already. In a big blue house exactly like ours. Walking our old dogs. Holding hands. Me asking her all the questions I’d never been able to before.

Mostly, I just wanted to know: "Did you know how hard we tried? Did you know how much we love you?"

Instead, I was in an ambulance. Someone spoke to me in English, and for a minute, I didn’t even understand it. My brain had to translate it, like I was hearing a foreign language. And it exhausted me like translating a second language does when you're unfamiliar. And this is weird... when English returned, the other language—the one from that place, the one I had written in—was gone. Completely gone.

I tried to hold onto the words. But they vanished. Like mist. One second I knew them all. The next? Nothing. It was like waking up from a dream and grasping at pieces before they disappear. And what I had written down so quickly? Gone. Just like the wise men said it would be.

Then the EMT said it: My daughter was alive.

Science can say what it wants—brain misfires, dying cells, whatever. But maybe it wasn’t just science.